When my BRCA test came back negative, that wasn’t the only reason I felt lucky. I felt lucky that I knew my family history for breast cancer. Without that awareness, the idea of genetic testing wouldn’t have occurred to me or my doctor.

I felt lucky that the BRCA test was financially accessible. It wasn’t always. I had chosen to forgo the test in the past because it was cost-prohibitive and not covered by my insurance; I had other financial priorities and obligations that felt more important at the time.

I felt lucky that my job had exposed me to the utility of genotyping. It prepared me to have a more informed and productive conversation with my Ob/Gyn.

I felt lucky to have a knowledgeable doctor who was able to walk me through my results and explain the implications of the additional routine testing available to me, given my higher risk score.

But here’s the thing: luck shouldn’t be the defining characteristic of anyone’s genotyping journey. For many patients with rare/and or life-threatening conditions- and the caregivers who support them-the journey to get to the right diagnosis can be arduous, frustrating, lonely, and expensive. While some specialists and genetic test providers are doing a good job of educating and empowering patients and caregivers, there’s still a great deal of work to be done.

At my agency, HCB Health, we work with a number of clients that have genetic testing at the core of their brand strategy. Through these partnerships, we’ve uncovered some recurring beliefs and behaviors that contribute to the current genetic testing quagmire. I’ve outlined them below with questions that we all need to think about and solve. Genetic testing is inherently good-the better informed we are about our own genetic makeup, the better equipped we are to make the best possible healthcare decisions for ourselves and our loved ones.

#1: Genetic testing is rarely offered as part of the diagnostic process, even less so absent family history.

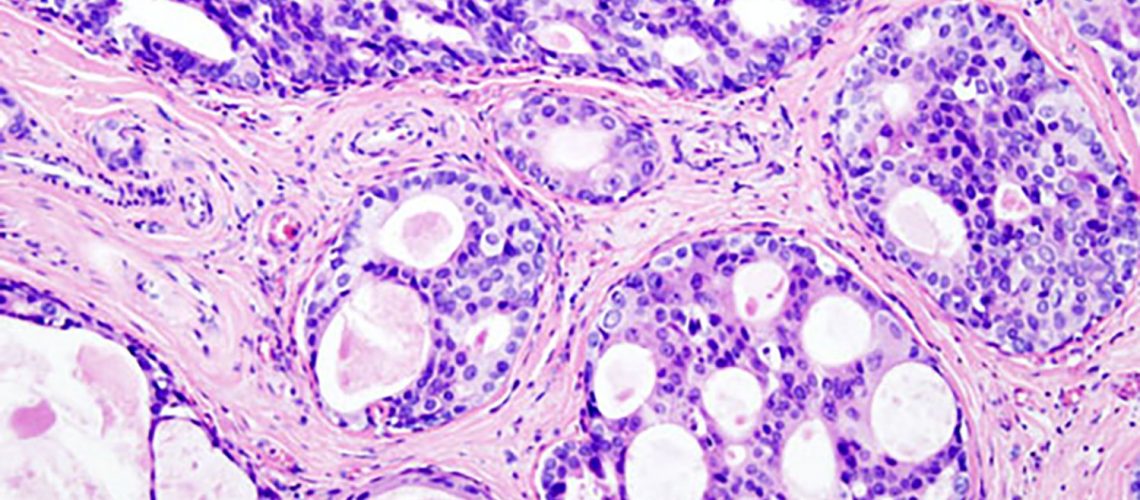

Genetic testing is available for more than 2000 conditions from more than 500 laboratories. Some specialties, such as obstetrics and oncology, are more accustomed to implementing genotyping as part of their standard operating procedure. Case in point; prenatal and hereditary cancer tests lead the pack, accounting for 63% to 73% of the total genetic testing spend, according to NIH.

But there are at least 7000 rare diseases that about 25-30 million Americans live with. While genetic testing doesn’t cover all of these yet, approximately 10 new genetic tests enter the market every day, adding to the 75,000+ that already exist. Additionally, new methods are rapidly being developed to improve accuracy and expedite the analysis of complex genomic data, making it a more compelling value proposition for healthcare providers who want to ensure the best outcome for their patients. How do we leverage this groundswell in scientific know-how and test availability to compel more HCPs to discuss and implement genotyping as routine practice for those who could benefit from a test?

#2: Few are aware that free genetic tests are often offered by pharmaceutical companies and/or advocacy groups.

The production cost of genomic sequencing has dropped dramatically, allowing more and more companies to cover what was primarily an out-of-pocket cost for patients in the past. Some payers also provide coverage and reimbursement, particularly for multi-gene tests, which are quickly outpacing single-gene tests due to the greater clinical utility of identifying more actionable mutations.

Don’t get me wrong, there are still plenty of out-of-pocket, patient-pay scenarios. But many of those situations correspond to elective procedures that are out-of-pocket to begin with, such as LASIK surgery or certain dental procedures. How can we create broader awareness about the accessibility of these tests and overcome cost reservations to drive greater HCP adoption and patient/caregiver demand?

#3: Testing is viewed as helpful only if there is an available treatment.

At face value, this makes a lot of sense. What’s the point of knowing, if you can’t do anything about it? But genetic testing offers so much more than just a binary diagnosis. It can help HCPs detect risk for disease, confirm a diagnosis, reclassify a disease, predict disease progression and prognosis, uncover hereditary genetic mutations, and guide overall health and treatment strategies.

Case in point; Years ago, my husband was clinically diagnosed with ankylosing spondylitis and initially treated with sulfa drugs (which, it turned out, he’s allergic to), followed by a daily prescription-strength NSAID for inflammation, pain, and stiffness. This treatment strategy worked at the time but we both knew it was probably not a long-term strategy. When an opportunity arose for him to receive free treatment though a clinical trial for an investigational biologic, he signed up and underwent the genetic testing required for inclusion. The test revealed that he did not have any genetic marker for ankylosing spondylitis. His diagnosis-and treatment-was wrong.

This happens more often than you might think. Additionally, treatments such as immunotherapies or biologics-even NSAIDs-can be potentially harmful to patients who do not need them. Genetic testing doesn’t just rule things in, it can reclassify diseases and even rule them out.

Genetic testing can provide critical inclusion and exclusion criteria for certain procedures, such as LASIK surgery. If you have a certain type of cornea dystrophy or keratoconus, LASIK surgery can further damage your vision. Having that genetic information ahead of time can help provide the best possible outcome for their patients. It allows them to devise a non-LASIK based treatment strategy to ensure the integrity of their patient’s vision for the future.

Genetic testing can also identify specific phenotype expression or genetic variants so HCPs can better predict disease progression and prognosis, and tweak their care management strategy accordingly.

Lastly, genetic testing can offer patients access to lifesaving investigational medicines, offer extended family members important medical histories that could impact their future and that of generations to come. How can we help educate around the breadth of actionable utility genetic tests offer for ourselves, our loved ones, or our patients?

Answering these questions won’t solve everything. The genetic counseling that often needs to accompany genetic testing can be a burden and a barrier for HCPs. How can we help HCPs either be more comfortable in this role or make it easier for them to quickly engage a genetic counselor? Misinformation around the privacy of genetic testing and effects on insurance is pervasive-and it can scare away both HCPs and patients. How do we ensure the facts are readily available so patients can be reassured that their personal genetic information will not be used against them? Then, there are the health policy implications and the debates over the most appropriate regulatory and payer coverage mechanisms.

I certainly don’t pretend to have all the answers, and I don’t mean to downplay the complexities that surround the genetic testing decision. But I do know that in this era of personalized medicine, genetic testing is here to stay. And I, for one, am excited about this potential, because at the end of the day, luck is not a very good strategy.